There is probably no policy that better defines modern Australia than Medicare. First legislated by the Whitlam government in 1974 as Medibank, Medicare guarantees free hospital services for public patients in public hospitals, and provides benefits for out-of-hospital medical services and most notably consultations with GPs or specialists.

Medicare was and is a positive transformational force in Australia, and is unquestionably the primary reason why I am a member of the ALP today.

Medicare has also been the most pronounced and consistent area of policy difference between the ALP and the Liberal party for more than four decades. Ideologically, the ALP believe in the importance of socialised healthcare, while the Liberals do not.

The challenge for the conservative movement has been working out how to reverse the effects of Medicare while claiming to support it, since it enjoys widespread support in the Australian population.

Following the close election result from last Saturday, the Coalition have been crying foul over Labor’s claims that the Liberals planned to privatise Medicare. Yet if we follow the principle that it is more important to judge people by what they do instead of what they say, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the Federal Labor campaign was 100 per cent correct. We just have to look at how successive Coalition governments have acted.

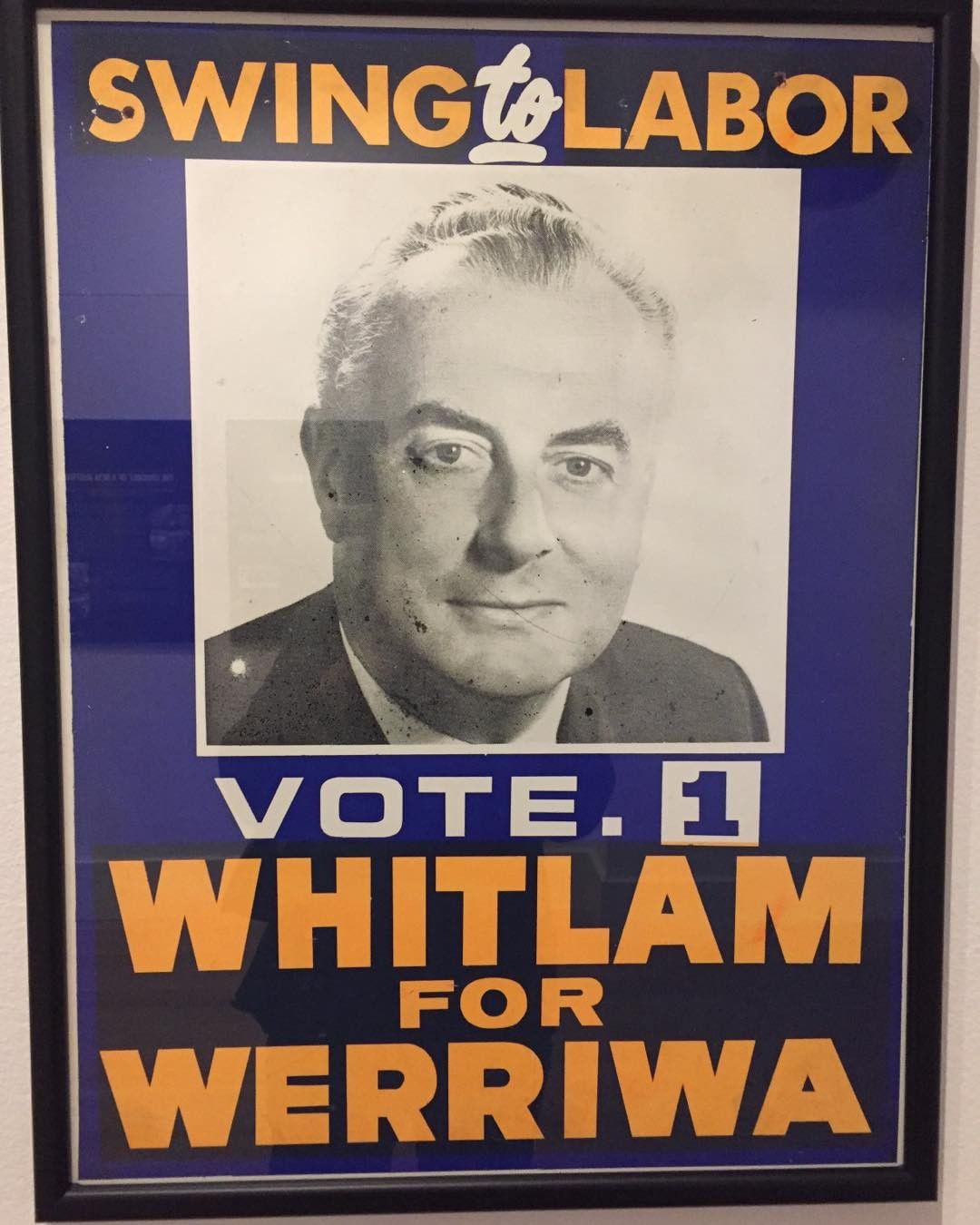

In 1975, Medibank commenced under Gough Whitlam. In 1976, Malcolm Fraser systematically dismantled Medibank. First, the government allowed people to opt out of paying the Medicare levy by holding private health insurance. Next, Medibank Private was set up, hospital agreements with states and territories were declared invalid, and bulk billing was restricted to pension card holders.

Finally in 1981, free health care was once again restricted to a small subset of the Australian population holding health care cards or meeting other strict criteria.

The Hawke government reversed almost all of these destructive changes in 1984, reverting to the original model under the new name of Medicare and retaining it with some minor funding changes for the next decade. Yet less than 12 months after Howard was elected, the Medicare Levy Surcharge and the Private Health Insurance Rebate were introduced to encourage people to return to the private health sector. By 2003, columnists in The Age were pointing out that the unrealistically low Scheduled Fees for GPs and incentives to only bulk-bill pensioners were once again undermining the universality of Medicare by stealth.

Post-Howard, it seemed that a strained consensus had been reached that both Medicare and the private health insurance system could co-exist. As one example, Kevin Rudd’s proposed Commonwealth takeover of the hospital system was focused on improving the public health system rather than undercutting the private health sector.

For the 2013 election, the Liberals put out policies that largely matched Labor’s platform, only to spring a completely unforeshadowed $7 GP co-payment on the Australian public the following year. Even after the switch to Malcolm Turnbull, the Coalition has continued to undermine Medicare, cutting bulk billing for pathology tests in the most recent budget.

Given all this, the ALP’s campaign to ‘save Medicare’ from the Liberals not only seems warranted but pretty restrained. I’m genuinely proud to be part of a party that believes in the importance of a strong public health-care system. The ideology of conservatives means that they simply can’t be trusted.

In the UK, David Cameron repeatedly and explicitly ruled out privatising the NHS (the UK’s Medicare equivalent), only to go on to significantly undercut the universality of their system through funding cuts and rationing of hospital and GP services to the public, leading to demonstrably worse care. As another example, the US private health system famously pays twice as much on its largely privatised health care system while having the lowest life expectancy of wealthy countries.

Medicare is not a guaranteed right for Australians. It has been revoked once and it could happen again if we don’t exercise our voting rights wisely.

The legendary writer and historian Harry Leslie Smith described life before public health care at a UK Labour conference in 2014. His speech continues to remind me why the fight for universal health care is still necessary today.